Charles Sear

- Born: 10 Jul 1816, Stewkley, Buckinghamshire, England

- Marriage: Sarah Bromwich on 16 Oct 1838 in Crick, Northamptonshire, England

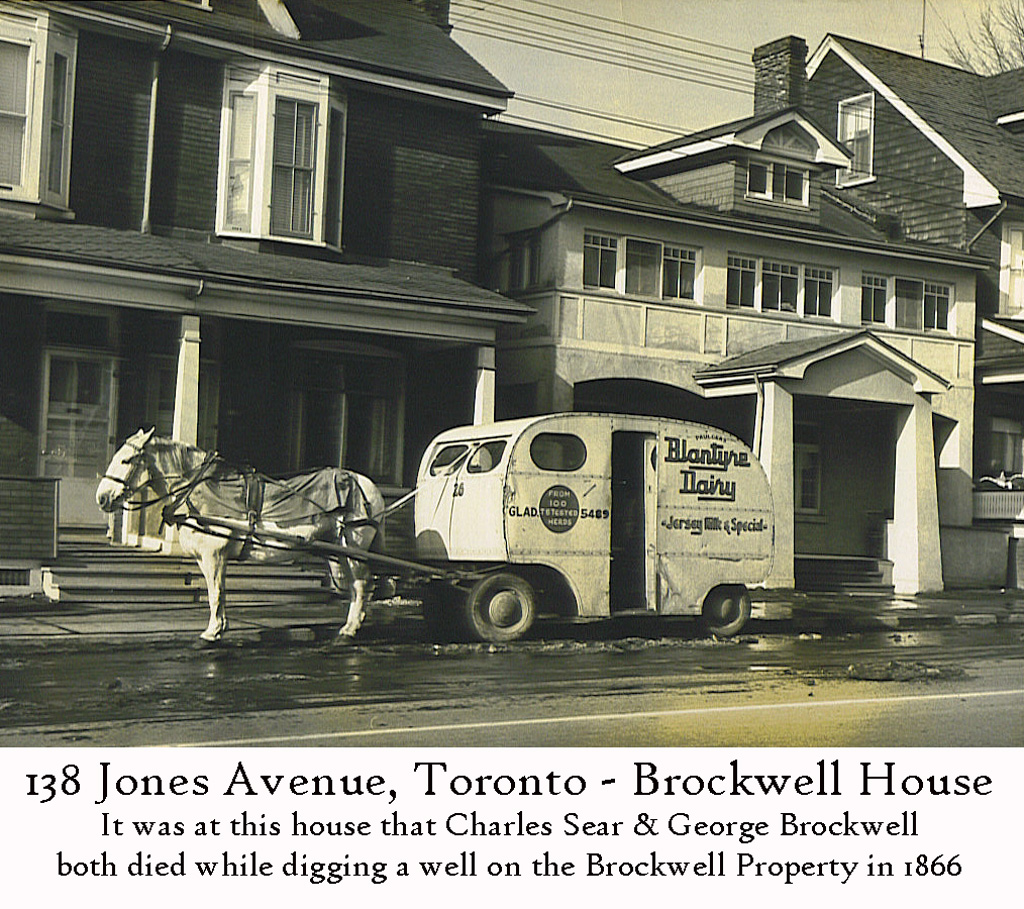

- Died: 1 Mar 1866, 138 Jones Ave, Leslieville, Toronto aged 49

- Buried: Saint John's Norway Cemetery, Toronto, Ontario

Cause of his death was Suffocation - Well Gas. Cause of his death was Suffocation - Well Gas.

General Information: General Information:

The following information on Charles Sear (who worked on the construction of the Kilsby Railway Tunnel) is courtesy of Gren Hutton - forwarded to me by Mary Finnegan - November, 2007.

********************************************************

1830s: Te Kilsby Railway Tunnel

Contributed by Gren Hatton

The digging of a tunnel 2400 yards in length was (and still is today!) a major engineering feat. And it was fitting that the work should have been put under the charge of one of the foremost engineers of the day - George Stephenson, famous son of the equally famous Robert Stephenson, the father of the steam locomotive. In the course of planning and supervising the work, Stephenson came to stay for a time in Kilsby. The house in which he lived was Cedar Lodge, on Main Road (now a Grade 2 listed building). In the garden of Cedar Lodge may still be seen a scale model of the tunnelmouth which he had built in concrete for the guidance of his work-force foremen (the model is Grade 1 listed, as it is felt to have even more historic significance than the house!). Other provisions were made to accommodate the rest of the work-force. The cottages on Manor Road, opposite the lower end of Church Walk, are believed to have been built at this time for some of the more senior construction gang workers. However, since Stephenson's work-force involved 1250 men and 200 horses, the problems of lodging and maintaining the work-force were considerable. Every barn and outhouse in the village was occupied by the navvies - and those who still remained had to build themselves makeshift turf-covered shanties in the fields, in which to sleep in wretched squalor. The effect upon the entire operation of the village of Kilsby was profound. F. B. Head, in his account of railway operating practice in 1849, recorded: "Besides the 1250 labourers employed in the construction of the tunnel, a proportionate number of suttlers and victuallers of all descriptions concentrated on the village of Kilsby. In several houses there lodged in each room 16 navvies; and as there were four beds in each apartment, two navvies were constantly in each, the two squads of 8 men alternately changing places with each other, in their beds as in their work." The influx of navvies brought its own considerable problems to the village. The labourers worked until the blood ran from their eyes - and when not working, their only recreations were drinking, petty theft, pitting dogs and cocks in illegal battle, and fighting amongst themselves. Trouble between the navvies and the Kilsby villagers was inevitable and frequent, and on at least one occasion the military had to be called in to restore order. However, the really memorable difficulties occurred not in the planning of the work and billeting of the work-force,but in the digging itself. To quote William Whellan's Gazeteer of 1849:

"Difficulties of an unusual character presented themselves during the completion of this tunnel. These arose from the existence of an extensive quicksand in the line of the tunnel. Extra shafts were sunk, and four powerful pumping engines erected, which continued to pump from the quicksand for six months, with scarcely a day's intermission, at the rate of 1800 gallons per minute, till at length the difficulty of tunnelling in the sand was reduced, though the operation was still one of extreme difficulty and danger. With the exception of the quicksand, it is cut through a succession of the hardest rocks; its cost was £300,000." The whole project was almost cancelled because of the apparently insuperable difficulties posed by the quicksand. By repeated borings in various directions near the planned course of the tunnel, the sand was discovered to be very extensive, and to be in shape like a flat-bottomed basin cropping out on one side of the hill. Certainly it was beyond the capability of the original contractors (J. Nowell and Sons), who gave up in despair and resigned their contract on 12th March 1836. Stephenson was working to a strict timescale and to a budget, and these were both severely upset by the delay and cost of the pumping work. The directors of the railway company were very properly concerned, and sent an observer - Captain Moorsom - to investigate on the spot. He suggested that Stephenson should call in assistance, but Stephenson would have none of it, and considered that he could overcome the quicksand. Though Moorsom was duly impressed by Stephenson's optimism and efficiency and put in a favourable report, the directors were still unconvinced; and when the pumping yielded no visible results after 13 months, they gave Stephenson an ultimatum - either to solve the problem within a further 6 months or have the project cancelled.

Stephenson persevered, with his 13 pumping engines and 12 steam engines; and if his pumps had not providentially begun to run dry at the very end of the additional six-month period, there is little doubt that the work would have been suspended - with consequences to the entire railway history of the country in general, and the Rugby area in particular, at which we can only guess. Stephenson himself had foreseen the problem of the quicksand. For the diggers of the Braunston and Crick canal tunnels, some 40 years or so earlier, had encountered exactly the same problems - and he tried to profit from their mistakes, by choosing a route for his tunnel as far to the east as possible. Unfortunately for him, his trial borings narrowly missed the quicksands and so failed to disclose the presence of the water under Kilsby Hill.

Eventually, however, and with due ceremony, the last of about 30,000,000 bricks was placed in position on 21st June 1838, just over four years after the first sod was cut; and shortly afterwards Kilsby Railway Tunnel was opened to commercial traffic - the first goods train passed through on June 24th, and the line was opened for passenger traffic on September 17th. Incidentally the George Hotel was rebuilt at about this time - it had previously been a stone building, but the new one was built of brick, like the tunnel. The new hotel retained the same name as its stone predecessor, which had been named after King George III since it stood alongside the turnpike road from Daventry to Lutterworth, established in the 1700s by an Act of Parliament signed by the King.

Research Information: Research Information:

The Following Information is Courtesy of Mary Finnegan - Downloaded from her Family Site at Ancestry.com on November 14, 2007.

"Charles was a civil engineer and was building the KILSBY tunnel. Kilsby is a village about 2 miles from Crick and that is where he met Sarah Bromwich, who was a lacemaker. Sarah's sister Mary was in service in Kilsby. There is a very significant tunnel at Kilsby on the Midland Railway (as it was then) line that runs from London to the East Midlands. The line goes north via Derby, which was a major centre for the Midland Railway."

It appears that the Sear family immigrated to the U.S. in 1855. By 1858 they were residing in Toronto. Sarah Anne Sear (born 1859) was their first child born in Canada.

While en route to the U.S. from England aboard the passenger ship "William Nelson" tragedy struck the family when Charles' and Sarah's daughter Elizabeth died en route, just 10 days short of her 12th birthday. Strangely, the two oldest children, Charles & John, were not aboard the ship and no trace of them (in North America has been found to date - Nov. 2007)

At least two children (Joseph & Caroline) returned to the U.S. to live permanently (Joseph in Pennsylvania & Caroline in Erie County, New York) after they both married their spouses in York County.

Medical Information: Medical Information:

Charles died while digging a well at 138 Jones Ave, Leslieville, Toronto.

Charles Sear passed away 1 of March 1886, after an accident that occurred while he was digging a well for George Brockwell - George was married to Louisa Wagstaff. Louisa was the sister in law of Charles' daughter Matilda (Sear) Wagstaff. George Brockwell also died in this well on the same day.

Some ask the question was it natural Gas or Marsh gas that smothered both Charles Sear and George Brockwell.

Charles' son in law, David Wagstaff, tried to save both Charles and George Brockwell but he was unsuccessful. David survived but was passed out for 5 hours after his unsuccessful attempt to save the two men.

Charles married Sarah Bromwich, daughter of John Bromwich and Jane Cowley, on 16 Oct 1838 in Crick, Northamptonshire, England. (Sarah Bromwich was born about 1820 in Crick, Northamptonshire, England, died on 30 Nov 1891 in Toronto, Ontario and was buried in Saint John's Norway Cemetery, Toronto, Ontario.) The cause of her death was General Debility.

|

Cause of his death was Suffocation - Well Gas.

Cause of his death was Suffocation - Well Gas.